by Tom Russo

It's mid-January in Los Angeles, and Dennis Venizelos is sitting in the studios of Marvel Films Animation, giving his take on the upcoming Spider-Man animated series. You start to wonder if he's talking about the show's violence factor -- sounds like we could be dealing with a too-militant web-slinger -- "90s hip" but out of character. Is television once again selling us a Spider-Man a dozen steps removed from the hero on the printed page?

Suddenly, all becomes clear. Venizelos, the art director on the series, is speaking of plans to make this a show told from the heights of New York City. Nosebleed -- as in nosebleed seats. Visually and thematically, he says, Spider-Man's latest TV incarnation is going to be like nothing ever seen before. Except in the comics.

Scheduled to air on Saturday mornings beginning

this fall, Spider-Man is the latest step in an ongoing crusade to

bring the Marvel Universe to the screen -- the right way. Like the hugely

successful X-Men animated series, Spider-Manwill run on FOX,

benefiting from the network's penchant for ground breaking programming.

Episode-to-episode continuity again will be the order of the day, offering

intelligent, dramatic storylines that put the kiddie cartoons to shame. But

Marvel's own involvement is arguably an even greater assurance of the show's

success.

Scheduled to air on Saturday mornings beginning

this fall, Spider-Man is the latest step in an ongoing crusade to

bring the Marvel Universe to the screen -- the right way. Like the hugely

successful X-Men animated series, Spider-Manwill run on FOX,

benefiting from the network's penchant for ground breaking programming.

Episode-to-episode continuity again will be the order of the day, offering

intelligent, dramatic storylines that put the kiddie cartoons to shame. But

Marvel's own involvement is arguably an even greater assurance of the show's

success.

Whereas X-Men is produced by Saban

Entertainment -- an independent studio which solicits Marvel's creative input

-- Spider-Man is the first show to fly directly under the new Marvel

Films banner, conceived and executed in-house, and "in-house," of course,

translates as "in control" when it comes to the way the wall-crawler is

portrayed.

Whereas X-Men is produced by Saban

Entertainment -- an independent studio which solicits Marvel's creative input

-- Spider-Man is the first show to fly directly under the new Marvel

Films banner, conceived and executed in-house, and "in-house," of course,

translates as "in control" when it comes to the way the wall-crawler is

portrayed.

"We're trying to take as many qualities as possible from the Spider-Man books and put them in the show," said Stan Lee, who's overseeing the project as executive producer and chairman of Marvel Films. "That, of course, includes the angst, the humor...Everything that we might do here is in the comic book itself."

"In some ways, we're in the unique position of doing exactly what Stan did in the comic back in the 1960s, which is to introduce elements that simply have not existed before in this particular medium," added John Semper, produced and story editor on the show. Melodrama, he said, is a comics fundamental sadly absent from TV animation. This shortcoming has tripped up earlier versions of Spider-Man and countless other programs.

"For lack of a better term, we're going to be doing a little bit of genuine soap opera," Semper said. "When Spider-Man gets up into the sky and he's fighting these super villains...what makes it unique is that he also brings with him the problems created down below when he was plain old Peter Parker. All of those romances, all of those disappointments and frustrations, are what makes his battles up above interesting."

Determined to keep Spider-Man in character, Semper

has actively recruited writers from the book to work on scripts for the show,

among them Gerry Conway. "When I was younger, I used to watch that [old

Spider-Man] series, and it always surprised me that, when the credits

rolled, I never saw the names of people who were currently doing the comic

book," Semper said. "That was astonishing to me, because these clearly were

the Spider-Man creators. I always said if I ever was in a position to do

it, the first guys I'd go to would be the ones writing the comic."

Determined to keep Spider-Man in character, Semper

has actively recruited writers from the book to work on scripts for the show,

among them Gerry Conway. "When I was younger, I used to watch that [old

Spider-Man] series, and it always surprised me that, when the credits

rolled, I never saw the names of people who were currently doing the comic

book," Semper said. "That was astonishing to me, because these clearly were

the Spider-Man creators. I always said if I ever was in a position to do

it, the first guys I'd go to would be the ones writing the comic."

By making good on this resolution, he said, he's already receiving script pages that have the Spider-Man persona nailed cold. Now, when the creative team and their hero make the perilous leap from the demands of comics to those of television, they won't be jumping blindfolded.

"It really is a tough thing -- to take a character whose life revolves around soap opera as well as action-adventure and to try to capture that in a [Saturday morning] show," Semper acknowledged. "But that's what ensures that when it's on the air, it's going to be revolutionary in terms of what it tackles and the way it tackles it. There aren't any other animated shows I can think of that have handled the personal lives of their characters with this degree of depth. The closest one is X-Men, but even that is still pretty much wall-to-wall action. And in Batman, you get into the mindsets of the villains a lot, but you never spend any time understanding what Bruce Wayne is going through. That's one of the things that doesn't work."

LIVE...FROM NEW YORK...

From Peter Parker's Chelsea bachelor pad to the Daily Bugle's offices overlooking Midtown, the Spider-Man saga has always been a New York story, an element which the television team has enthusiastically embraced. "We want Spider-Man to have a contemporary live-action feel," Supervising Producer Bob Richardson said. "This should have a reality to it that's more like NYPD Blue than The Smurfs. In the comic it's always been very evident that New York is where the story takes place, so we're making that very evident, too."

Because of Spider-Man's highly specific urban setting, Semper added, the program will be better equipped than most to introduce weighty subject matter. Too often, he argued, "issue-oriented" animation scripts ultimately produce "a forced, in-your-face kind of show. In Spider-Man, you can do a show about a serious issue without it looking out of place, because that's the world in which he lives, and it makes sense," Semper said, as opposed to "The Fantastic Four, where a lot of the adventures take place out in the galaxy, and universes are eaten like popcorn by Galactus. Ours is a much smaller world, and we can tackle issues that are closer to home."

Rooting Spider-Man in virtual

geographic reality involves no small amount of visual research. Background

illustrators thumb through photo collections with titles like Above New

York and The Rooftops of New York. Maps are consulted, then consulted

again. Recently, painstakingly rendered animation cels depicting Manhattan's

Pan Am Building were scrapped, as the California-based art staff learned

the Midtown landmark had gotten a new tenant -- and a new sign -- more than

a year ago.

Rooting Spider-Man in virtual

geographic reality involves no small amount of visual research. Background

illustrators thumb through photo collections with titles like Above New

York and The Rooftops of New York. Maps are consulted, then consulted

again. Recently, painstakingly rendered animation cels depicting Manhattan's

Pan Am Building were scrapped, as the California-based art staff learned

the Midtown landmark had gotten a new tenant -- and a new sign -- more than

a year ago.

"It's a challenge getting all the places right," Richardson conceded. Still, he said, the animators aren't about to dump their star into some generic, cookie-cutter backdrop. They want the wall-crawler swinging across a cityscape that's as authentic and alive as the New York in a Martin Scorsese film.

"In the shows that were done before, it always felt like the city was empty," Richardson said. "Our feeling is, let's populate this city, let's make it so that when you're down at street level, there are crowds of people and cars going by. And then the picture moves up the side of a building, and there's Spider-Man. So you get that contrast."

Just watch out for vertigo. Venizelos and Richardson said they'd like to work three-dimensional effects into the series wherever possible, giving Spider-Man's action sequences an appropriately precarious P.O.V. Take the Letterman show's new bird's-eye-view opening, insert a guy in costume swinging by on a web line, and you get the idea.

"The previous shows were very flat,"

Richardson said. "You didn't get the kind of 'hanging-above-the-city' feel

that really should be there with a character like Spider-Man. You should

get butterflies in your stomach [while] watching, because that's what comes

with hanging from the top of a 60-story building."

"The previous shows were very flat,"

Richardson said. "You didn't get the kind of 'hanging-above-the-city' feel

that really should be there with a character like Spider-Man. You should

get butterflies in your stomach [while] watching, because that's what comes

with hanging from the top of a 60-story building."

As Venizelos and his animators readied the series' initial episodes for production, they were still determining how this 3-D look would be achieved. They'll start with a process known as wire-framing, in which they "build" skeletal models of skyscrapers and other backdrop elements on a computer screen. But, unless Spider-Man is going to be weaving his way through a construction site, these skeletons need to be completed. Color and texture must be mapped on to the models to give them "walls."

For crispness and cel-to-cel consistency, the ideal would be to generate these building facades completely by computer, Venizelos said. In the end, though, a more conventional method involving some hand-painting is likely to prove the viable choice. "The technology is out there. It's just a matter of having the money to do it, because it's kind of expensive right now," Venizelos said. Still, he added, "When production first starts on any show, the animators always have good intentions. This is one show where those intentions will be carried out."

DESPERATELY SEEKING SPIDEY

One happy dilemma the art team

has wrestled with is deciding which comics stylization will serve as a model

for the show. Over the decades, some of the greatest names in comics have

drawn the web-slinger -- the progression, of course, is legend: Steve Ditko

took a scrawny high-school science nerd and made him a super hero, John Romita

and Gil Kane gave him some muscle, and later, Todd McFarlane contorted his

battle pose in a way that italicized the "spider" in Spider-Man. Whose lead

should the animators follow?

One happy dilemma the art team

has wrestled with is deciding which comics stylization will serve as a model

for the show. Over the decades, some of the greatest names in comics have

drawn the web-slinger -- the progression, of course, is legend: Steve Ditko

took a scrawny high-school science nerd and made him a super hero, John Romita

and Gil Kane gave him some muscle, and later, Todd McFarlane contorted his

battle pose in a way that italicized the "spider" in Spider-Man. Whose lead

should the animators follow?

"Basically, they're all good," said Stan Lee, who collaborated with the best of the best, "but in the past few years, I've learned a little more about animation than I used to know, and it's more than taking a certain artist's style. You have to take something that will look good in motion and doesn't have too many lines to it...There are so many considerations that by the time we're finished and we feel this is the look of the show, it's really an amalgam of everybody's style. We may like the way somebody handles legs, or the mask, or facial expressions...We take a little bit from each one.

"It'll be Spider-Man, but it will have its own unique animated look," he continued. The Fleischer-esque animation in Batman has been comparably derived, he said. "While the Batman show has the dark mood of the movie and of Frank Miller's style, the art doesn't look like Frank Miller's or, indeed, like any other artist's. It has its own look."

The writing staff has a similar mandate to reconcile

past and present as they cull from the comic's rich history. Script plans

call for Spider-Man to tangle with villains ranging from the Green Goblin

and Doctor Octopus to Hobgoblin, Kraven, The Vulture, and Venom -- all in

present time. Establishing Peter Parker as a college-age hero is the first

step in a complicated process of making the show's story logistics work.

The writing staff has a similar mandate to reconcile

past and present as they cull from the comic's rich history. Script plans

call for Spider-Man to tangle with villains ranging from the Green Goblin

and Doctor Octopus to Hobgoblin, Kraven, The Vulture, and Venom -- all in

present time. Establishing Peter Parker as a college-age hero is the first

step in a complicated process of making the show's story logistics work.

"A comic book is an interesting creature, because it's sort of bits and pieces," Semper said. "If it involved one author setting out to do one magnum opus, there might be an overall story arc that would tie the universe together more tightly. In the case of Amazing Spider-Man, you've got close to 400 comic books, all from different eras, all written by different writers, drawn by different artists, and edited by a lot of different people.

"What we get to do at this particular point," he said, "is walk in after a body of work has been completed and say, 'Let's take all of these different stories and elements, but now let's approach it from the point of view of having a fixed number of episodes, and let's fill in the holes and make it head in a specific direction.'"

While honoring Spider-Man's roots,

Semper argued that the show's need for cohesion rules out "slavish adaptations"

of the comics. In some ways, he said, there may actually be room to improve

on the classics. He cited a planned wrinkle in the Scorpion's origin as a

case in point.

While honoring Spider-Man's roots,

Semper argued that the show's need for cohesion rules out "slavish adaptations"

of the comics. In some ways, he said, there may actually be room to improve

on the classics. He cited a planned wrinkle in the Scorpion's origin as a

case in point.

"When Farley Stillwell creates the Scorpion, he uses a technology we're calling Neogenics," Semper said. "Well, let's assume that Neogenics is really quite an amazing discovery. Even after the Scorpion story, other people come along and start tinkering with it, because it's new and exciting and was invented and researched at Empire State University. This can subsequently serve as an explanation for things like Curt Connors turning himself into the Lizard. So now you've got a link between two completely separate stories that never had any kind of link before, and yet the link is a very logical one.

"You start to justify why so many weird creatures and villains turn up in New York all of a sudden," Semper said. "You start to get a feeling that, 'Hey, there's a universe here.' It requires a lot of headwork. You've really got to create that universe very completely, or it's just not going to hang together very well."

THE DREAM TEAM

In today's market, the cost of building a new

universe is substantial. According to Avi Arad, chief of Marvel Films and

an executive producer on the show, a single 30-minute episode of

Spider-Man will cost roughly $400,000. That's part for the course

that X-Men and Batman play, but about $125,000 more than the

average half-hour cartoon.

In today's market, the cost of building a new

universe is substantial. According to Avi Arad, chief of Marvel Films and

an executive producer on the show, a single 30-minute episode of

Spider-Man will cost roughly $400,000. That's part for the course

that X-Men and Batman play, but about $125,000 more than the

average half-hour cartoon.

It's far more difficult to put a price tag on the human effort. That saga begins with X-Men, whose success sparked FOX's interest in picking up a companion show. Perhaps the most enthusiastic cheerleader was FOX Children's Network President Margaret Loesch, who previously headed the Marvel Productions animation production venture in the 1980s. Loesch felt so strongly about Marvel's new "stick to the comics" approach that she put in an order for 65 episodes of Spider-Man. By the fall of 1995, the show will have a large enough rotation to move from Saturday mornings to weekdays.

At the same time, the prospect

of returning to a retooled, in-house Marvel production operation proved

attractive. With the newly appointed Arad leading the way, Marvel Films opened

its doors last June. "There's a comfort in having the producer, the art director,

Stan Lee, and myself on the same floor," Arad said. "It's a fan group, all

in one spot, and all committed to the same thing."

At the same time, the prospect

of returning to a retooled, in-house Marvel production operation proved

attractive. With the newly appointed Arad leading the way, Marvel Films opened

its doors last June. "There's a comfort in having the producer, the art director,

Stan Lee, and myself on the same floor," Arad said. "It's a fan group, all

in one spot, and all committed to the same thing."

The process of assembling a full production unit continued well into 1994, with much of the effort focused on reviewing portfolios. The bulk of those came from the ranks of storyboard artists and background designers -- people responsible for the models which guide the show's animators. Those who are hired form the core of a studio staff that will eventually number about 60 persons.

Although comics-trained talent isn't prevalent, Richardson said, the Marvel Films group does include artists like Del Barras, whose work most recently appeared in Marvel UK comics, and who will be one of the series storyboard artists. Primarily, though, the resource pool will be folks from television. "We've got people who've worked on Batman, X-Men, and a lot of different shows that have been done over the years," Richardson said. "We're drawing from among those guys, as well as others who may not have been working on super-hero stuff for some time but who are very much capable of doing that."

The animation itself will be done in Japan, home to some of the hottest facilities in the industry. Hundreds of illustrators will produce the drawings that literally bring Spider-Man to life -- some 15,000 to 20,000 cels per episode. As Venizelos noted, Marvel's choice of studio (still TBA) won't have been made lightly.

While the art staff was comparison shopping overseas, Semper was busy gathering his Spider-Man writing team so that there would be stories to animate. He was also making final revisions to the Spider-Man "bible," a 100-page writers' manual conceived to keep character development on track. Even for veteran wall-crawler scribes, the volume offers a fresh perspective on the hero and his supporting cast. Take, for example, Semper's analogy between Spider-Man and a disaffected James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause: "Like Peter Parker, [Dean] is very reactive...You always know that deep down inside, even though he isn't showing it, he's really seething with angst, frustration, anger, and raw energy."

HOW DO YOU SAY "THWIP"?

As finished scripts roll in and episodes begin to return from the 15- to 20-week animation process, Richardson said, key decisions about the sound of Spider-Man will be finalized. Sound, ultimately, is one of the few areas where the show can't draw on its comic book source material. Music composers will be auditioned, and actors will be signed to give voice to the characters. Viewers who get a charge out of celebrity voice talents who star in animated projects won't be disappointed by the Spider-Man roster and, thanks to the trend set by FOX's The Simpsons, additional celebrity cameos may also be on tap.

And when it comes to plot, Semper keeps the phone lines to New York wide open. His point man in Marvel editorial is Spider-Man Group Editor Danny Fingeroth, who called his role as a consultant on the show "comparable to Bob Harras's on X-Men. I read and advise on the stories and teleplays, and give them input on keeping things true to the characters."

"They keep you honest," Semper said of his colleagues back east. "When you start to do something that isn't spider-like, there are a lot of people around who will say, 'No, no, no, that's not right,' or 'Hey, why isn't Spider-Man's spider-sense working here?' That's the kind of thing that these guys are really wonderful for. They have a very good sense of what the character should be up to at any given moment."

This is what Marvel Films has striven for since its inception: to stay true to comics form. This is why Stan Lee and Avi Arad sought out a network that values the Marvel Universe for what it is. This is why Marvel opened its own studio. This is why, above all, the show seeks to capture the melodramatic essence of Marvel's signature creation. "It's one thing to have a super hero fight a guy flying around on a bat jet throwing pumpkin bombs," Semper said. "But it's another thing when the guy throwing the pumpkin bombs happens to be the insane father of the super hero's best friend in private life.

"If we don't have those kinds of complications, then we don't really have Spider-Man."

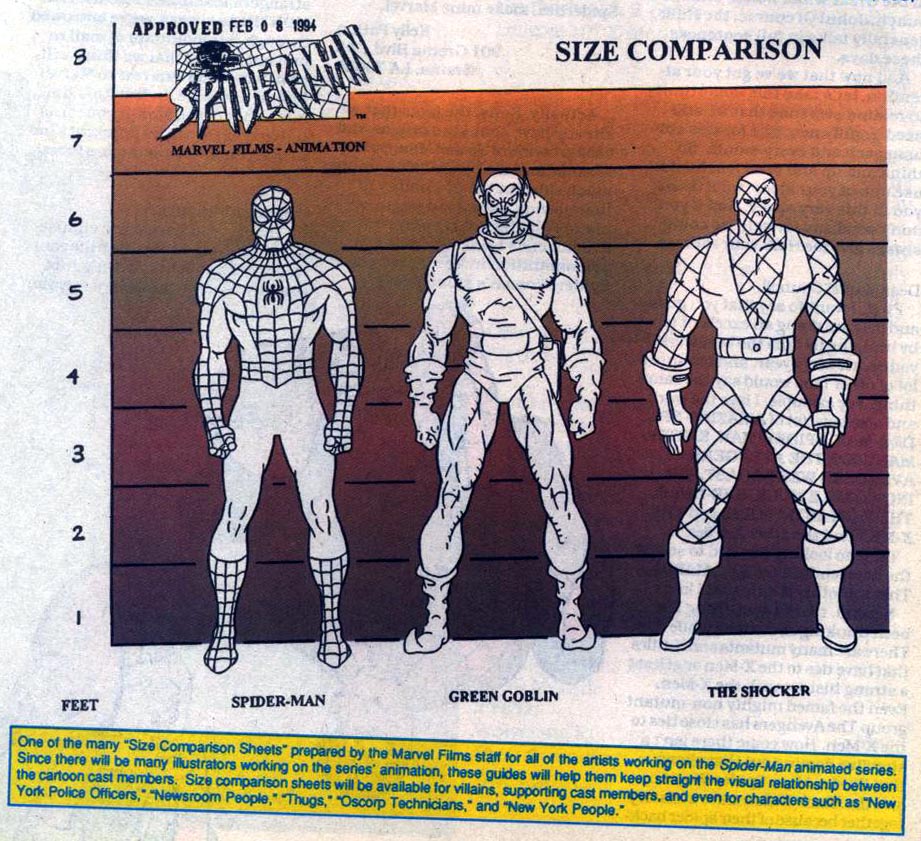

Official Model Sheet Size Comparisons

This page is a part of DRG4's Marvel Cartoon Pages:

Featuring Spider-Man, X-Men, Fantastic Four, Iron Man, Incredible Hulk, and the Silver Surfer.